Mr. Chan Lok-choi, Hong Kong’s last known handmade bird cage maker, repairs a broken bird cage at his stall in Yuen Po Street Bird Garden, Mong Kok.

Handmade bird cages:

a swansong

for the ages

A

multi-coloured parrot perches on a wooden log; two snow white birds endearingly

ruffle their feathers; other songbirds give high-pitched chirps of “hello” to

unsuspecting passersby. This is Yuen Po Street Bird Garden, otherwise known as

the home of the songbirds. It is here that I find dozens upon dozens of lively,

energetic birds—albeit many in cages—and it is also where I find, quietly

sitting in his stall, Hong Kong’s last known handmade bird cage maker.

Around his waist he wears a half apron, and the concentration with which he works is simply unwavering. As I approach him, he’s working on adding a new piece of bamboo to fill the empty space in a broken bird cage, delicately but efficiently measuring and trimming.

Around his waist he wears a half apron, and the concentration with which he works is simply unwavering. As I approach him, he’s working on adding a new piece of bamboo to fill the empty space in a broken bird cage, delicately but efficiently measuring and trimming.

The bird cages in Mr. Chan’s shop, including ones that are repaired and awaiting repair. One bird cage houses a young green songbird.

For those in the know, Mr. Chan Lok-choi isn’t an unfamiliar name or face; after all, the master craftsman, or 師傅 in Cantonese, has been sitting in this precise shop for over 20 years. And for two hours, I sit alongside him as he nimbly conducts repairs, which take up most of his daily practice nowadays. While many Hong Kong people still own birds, most people aren’t buying new handmade bird cages anymore, he says simply, but he thankfully equally enjoys process of both making and repairing cages. “There’s a level of satisfaction [in repairs]. When it’s broken in a difficult way, and I’m able to fix it in an ideal manner, I’m really happy,” he tells me.

“There’s a level of satisfaction [in repairs]. When

it’s broken in a difficult way, and I’m able to fix it in an ideal manner, I’m

really happy.”

Below: Mr. Chan shapes a piece of bamboo to fix a broken leg on a bird cage.

Left: Filing the bottom of the bird cage to make the surface even.

Mr. Chan first learned how to make bird cages by hand from his uncle in 1955, before following the footsteps of master craftsman Cheuk Hong. Back then, bird keeping was much more popular, with the tradition having begun during the Qing dynasty. The practice soon carried over from China to Hong Kong, and since birds were easy to take care of in small spaces, and were allowed in public housing estates (as opposed to dogs and cats, for example), many Hong Kongers adopted them as pets and would also bring them on walks, on public transport, and to dim sum restaurants.

I ask Mr. Chan if he has a favourite design, and he enthusiastically shows me one of his prized cages (shown left), which he says is the only one to exist in this world. Prized is an apt way to describe it: this bespoke creation features a top that likens it to a crown, an extra structural layer that doesn’t exist on any other bird cage I see in the Bird Garden. (For a less royal comparison, Mr. Chan jokes that it looks like a Mongolian ger.)

Even as pet birds—and subsequently, handmade bird cages—fall out of favour in Hong Kong, Mr. Chan’s loyalty for bird cage making remains steadfast. While he once tried his hand at advertising and even made makeup products, he always returned to bird cage making. With his self-assured demeanor, he strikes me as an artist in its purest definition—someone who simply loves his practice.

“There’s no one to teach. No one will learn.”

As Mr. Chan painstakingly cuts and shapes pieces of bamboo—with a band-aid on his thumb, no less—he talks me through his processes and tools, all of which are custom made and ordered, he says. There’s his array of knives and carving tools, which he uses to widen and create holes in the bird cage frame, to file or trim away broken parts, and to shape the ribs. There’s the gas lamp (“You’ll have seen this type of lamp in movies, but they never show this design,” he affectionately says), which he uses to soften and bend the bamboo, and another tool that he uses as a manual drill to create circular holes in the bird cage door frame. Of course, he has another supplement: glue, which he actually chastises. He only uses it when it’s absolutely necessary: “If you use glue, you’re not a real craftsman,” he says. “If you don’t use glue, then you’re a real craftsman.”

Three different repair processes: reattaching the handle; creating a hole in the bird cage door; widening the hole to make it fit the bamboo rib. Mr. Chan adapts his skills and techniques based on the type and levvel of repair each bird cage requires; no one process is exactly the same.

While Mr.

Chan answers all my questions with patience, it’s no surprise when he tells me

about how he was quiet as a schoolkid. Indeed, he exhibits an introverted

nature, one that is especially fitting for a profession that requires him to

sit for hours on end, mostly in solitude, save for a few chats here and there

with customers and neighbouring bird garden stall owners.

Regardless, Mr. Chan comes across as very content, and it is abundantly clear that he is deeply engrossed in his practice, even though he clearly knows the tradition of hand making bird cage is dying. “There’s no one to teach. No one will learn,” he says. While hobbyists do take classes from him, he recognizes it’s near impossible to make a decent living doing the work that he does on a daily basis, especially to his standards of quality as well. Birdkeeping and handmade bird cage making, as we know it now, is inevitably going to fade with the loss of the older generation.

1 / Some of Mr. Chan’s many tools, including paintbrushes, screwdrivers, and other knives and carving tools. While there’s one ruler included in his kit, I notice that Mr. Chan actually never uses it—he opts to rely solely on his eyes and understanding of the bamboo frame to conduct his repairs.

Regardless, Mr. Chan comes across as very content, and it is abundantly clear that he is deeply engrossed in his practice, even though he clearly knows the tradition of hand making bird cage is dying. “There’s no one to teach. No one will learn,” he says. While hobbyists do take classes from him, he recognizes it’s near impossible to make a decent living doing the work that he does on a daily basis, especially to his standards of quality as well. Birdkeeping and handmade bird cage making, as we know it now, is inevitably going to fade with the loss of the older generation.

1 / Some of Mr. Chan’s many tools, including paintbrushes, screwdrivers, and other knives and carving tools. While there’s one ruler included in his kit, I notice that Mr. Chan actually never uses it—he opts to rely solely on his eyes and understanding of the bamboo frame to conduct his repairs.

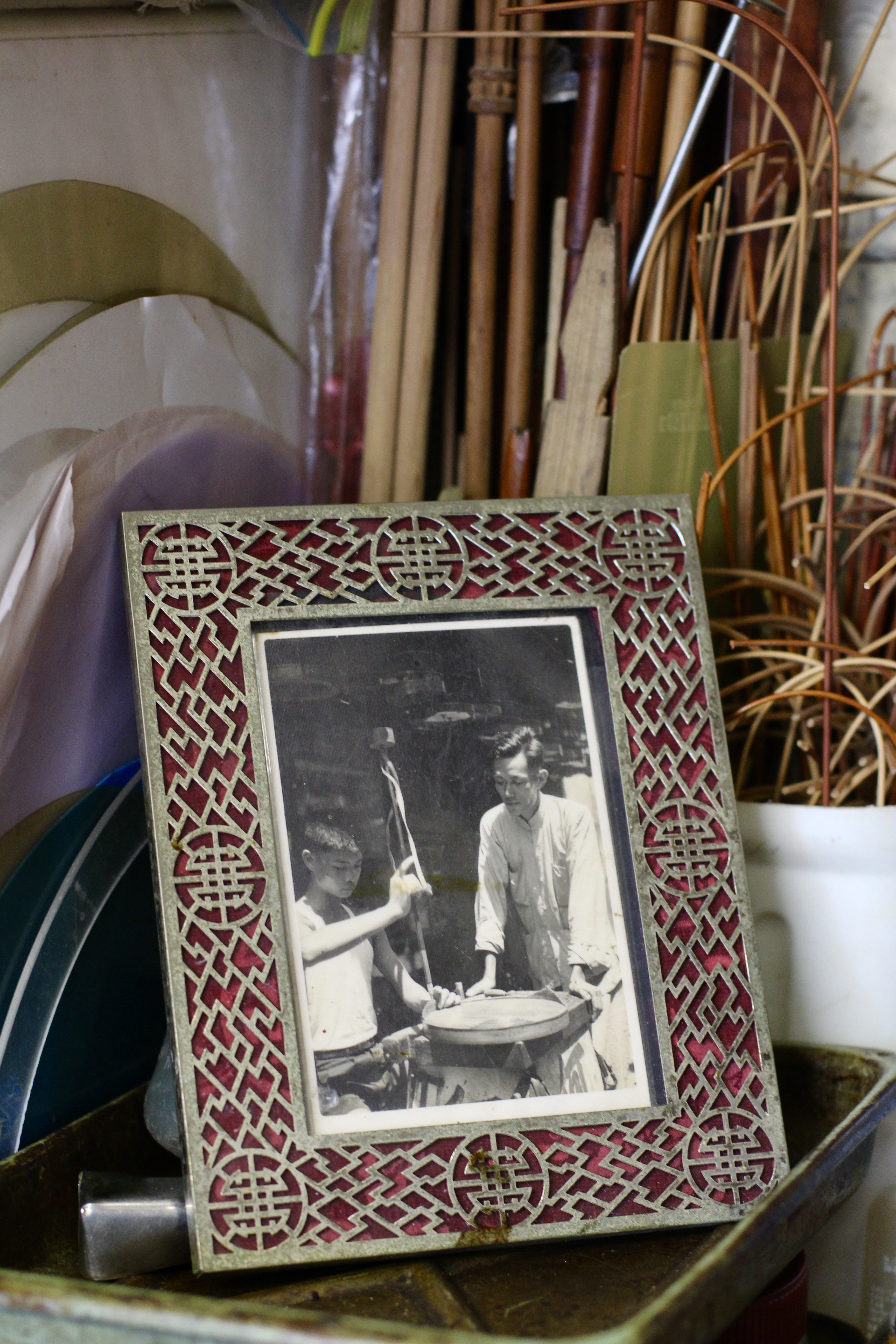

2 / A picture of the young Mr. Chan alongside his teacher, master craftsman Cheuk Hong.

3 / Mr. Chan uses the gas lamp to loosen the bamboo frame.

Snapshots from Yuen Po Street Bird Garden.

“If you don’t work hard and suffer, if you just play around, you won’t achieve success.”

Shortly before

I leave his stall, Mr. Chan offers some wisdom as he reflects on how no one

wanted to solicit his services when he was still an apprentice. In English, it

doesn’t feel quite as poignant, but a rough translation of his remark goes: “If

you don’t work hard and suffer, if you just play around, you won’t achieve success.”

This comment is perhaps a light critique of today’s Hong Kong youth, but it makes me consider how Hong Kong’s economic and technological advancements have significantly altered our culture and society, and understanding of success. In the past, a chosen profession meant that you worked hard so that you could stay in that business for the rest of your life; now, that same determination isn’t nearly as widespread. Mr. Chan’s simplistic mentality embodies a dissipating ideology, one that values uncomplicated personal fulfillment over nominal achievements or society-set notions of apparent success.

This comment is perhaps a light critique of today’s Hong Kong youth, but it makes me consider how Hong Kong’s economic and technological advancements have significantly altered our culture and society, and understanding of success. In the past, a chosen profession meant that you worked hard so that you could stay in that business for the rest of your life; now, that same determination isn’t nearly as widespread. Mr. Chan’s simplistic mentality embodies a dissipating ideology, one that values uncomplicated personal fulfillment over nominal achievements or society-set notions of apparent success.

And with that, I say goodbye. The songbirds’ chatter

sends me off, and Mr. Chan quietly continues his repairs.

© 2020 Mabel Lui