Carved in history: the last of Hong Kong’s hand-carved mahjong

For someone who surrounds himself with mahjong tiles

every day, it may come across as a surprise to learn that Mr. Cheung Shun-king

doesn’t actually know how to play the game. “I don’t have time to play,” he reasons.

That’s because he sits and works at his shop every single day—including weekends—from 11 in the morning to 11 at night. One of Hong Kong’s last mahjong tile carvers, Mr. Cheung has been at his Jordan shop for over 20 years, where he has made hand-carving cream and white tiles a quotidian practice. I watch as he moves swiftly, etching characters onto the mahjong tiles with finger-sized blades, dotting paint into the indentations of dice, and cleaning off imperfections with a scraper and remover oil.

That’s because he sits and works at his shop every single day—including weekends—from 11 in the morning to 11 at night. One of Hong Kong’s last mahjong tile carvers, Mr. Cheung has been at his Jordan shop for over 20 years, where he has made hand-carving cream and white tiles a quotidian practice. I watch as he moves swiftly, etching characters onto the mahjong tiles with finger-sized blades, dotting paint into the indentations of dice, and cleaning off imperfections with a scraper and remover oil.

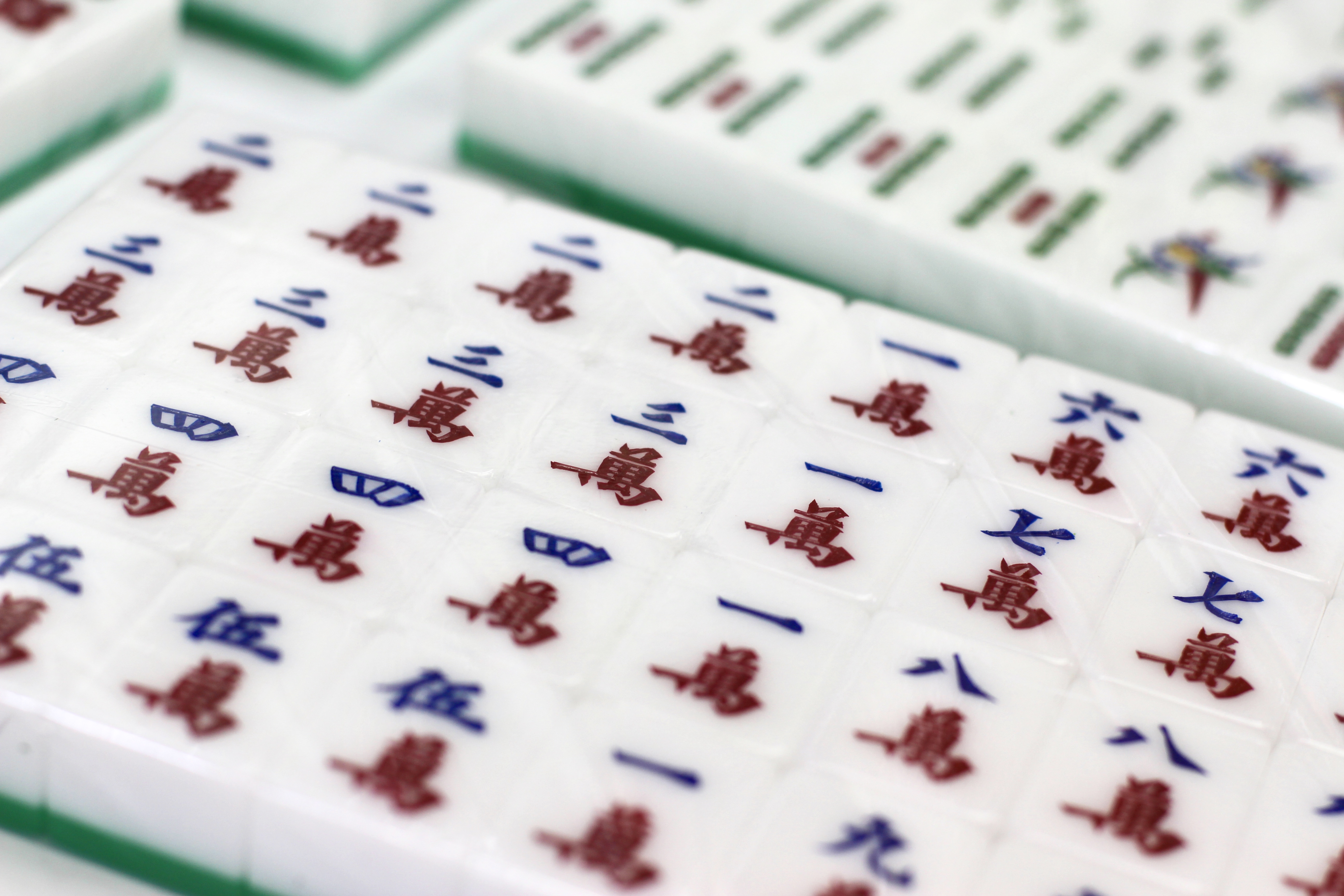

Above: Mr. Cheung Shun-king’s hand-carved mahjong tiles. Shown here are the character tiles representing numerals, painted with blue and red. This particular set features white tiles with a green backside, which is one of the traditional colourways of mahjong sets (the other is all cream).

Above: A set of cream-coloured mahjong tiles, freshly carved.

Right: Mr. Cheung’s makeshift carving tools, including several knives and blades.

Right: Mr. Cheung’s makeshift carving tools, including several knives and blades.

While he never officially followed a master craftsman, Mr. Cheung learned the trade from his father and grandfather, and has continued the generational legacy. But similar to other craftsmen I spoke to, he is unapologetically honest and pragmatic in considering the future of his business. “People aren’t playing mahjong [as much] anymore. Hand-carved is expensive, and China makes them really cheap,” he says. “Nowadays, most people choose to buy the cheapest sets, whereas in the past, most people chose to buy the highest quality set.”

The game of mahjong has been ingrained in Hong Kong’s daily culture. Even when gambling was banned in China in 1949, mahjong continued to rise in popularity in Hong Kong, which manifested in the establishment of mahjong parlours and gambling dens. Now, mahjong exists in more private spaces, but it continues to make appearances everywhere from family gatherings and celebrations in hotels to loud street markets.

Mr. Cheung cleans up the paint on a custom order of hand-carved dices at his shop, Biu Kee Mahjong, which is named after his father.

Here, he’s just finished scraping off the residual paint on some custom dice and is about to wipe the dice clean with remover.

Here, he’s just finished scraping off the residual paint on some custom dice and is about to wipe the dice clean with remover.

“People

aren’t playing mahjong [as much] anymore. Hand-carved is expensive, and China

makes them really cheap. Nowadays, most people choose to buy the cheapest sets, whereas in the past, most people chose to buy the highest quality set.”

Mr. Cheung works at his shop every single day, other than the

first two days of Chinese New Year.

first two days of Chinese New Year.

Carving the Chinese character for seven (七) onto a mahjong tile.

Painting the grooves of a carved dice. Aside from mahjong tiles, Mr. Cheung also takes custom orders for dices of varying sizes.

And though Mr. Cheung certainly has affection for the hand-carving craft, he isn’t precious about adapting with the times, which is why customers will be able to find machine-carved mahjong tiles that feature an array of untraditional colours and other mahjong-related items at his shop as well. Sometimes, people just want to pay less to play, and to Mr. Cheung, that’s okay. For him, the decision to sell both hand-carved tiles and machine-carved ones was a purely economic one; after all, he says, he has to earn money.

I find the concession bittersweet, but I certainly understand the perspective, as Hong Kong’s sky-high rent mandates high profit margins for any business that hopes to survive. Mr. Cheung comments that Hong Kong’s youth are playing mahjong with their phones now, and naturally, with technological advancement comes less demand for traditionally handmade products.

“Surely, there are still people who play mahjong—but the young ones play on their phones, so they play individually. … They don’t play with the real tiles, so I’m making them less and less.”

Mr. Cheung also fulfills many personalized orders and requests from clients, which are ordered as gifts or commemorations of special occasions. Each custom mahjong tile with a Chinese character goes for $100 HKD, while special designs go for $300 HKD and up. Shown above is his array of custom mahjong tiles for which he made mistakes and therefore couldn’t sell (though frankly, it’s very difficult to tell upon first glance).

In this vein, I ask Mr. Cheung if coronavirus has affected his business over the past months. Contrary to my

expectations, he says that business was actually really good in the beginning of

the year. “It had nothing to do with me though,” he clarifies. He offers the conjecture

that people were spending more time at home during quarantine, so they were more willing to spend

money to buy sets.

Left: Mr. Cheung cleans up the paint on a hand-carved dice with remover.

Below: Some of custom mahjong tiles Mr. Cheung has carved. Of these, he said the tiger was most difficult.

![]()

Above: Miscellaneous mahjong-related items that Mr. Cheung also sells in his shop, including playing cards, gambling chips, and more.

Perhaps, then, there is still hope for some remnants of this heritage to be preserved, but I can’t say that I’m holding my breath. After all, the admission that no youth are continuing to keep these cultural practices alive—and for that matter, all the craftsmen’s acceptance of this collective loss—feels directly indicative of what will happen to Hong Kong and its distinctive identity. To me, the gradual disappearance of these traditions mirrors our political trajectory, portending a forced acceptance of what will be, not necessarily what we wanted Hong Kong’s future to be. Just like how Mr. Cheung has resorted to selling both hand-carved and machine-made mahjong, it seems that Hong Kong will have to accept our imminent loss of this Cantonese identity, and succumb to integration with China.

Personally, as someone who has grown up in this city and lived the values of a free society, my heart is constantly breaking from the processing the reality that Hong Kong’s independence, identity, and culture—whatever little of it we have left—is being subject to persistent erosion.

Miscellaneous mahjong paraphernalia displayed in a glass class at the front of Biu Kee.

“Before, there was truly a lot of people who played

mahjong, so there was business. Now, there’s no business.”

Similarly, the city’s remaining artisans can’t escape from the knowledge that their craft will disappear. True resistance is futile, so Mr. Cheung has adopted a practical approach and outlook instead. His chatty persona has allowed him to become acclimated with media appearances and interviews, which has helped promote business and interest in the local craft from locals and foreigners alike. He teaches classes in schools to educate young students about the process of hand-carving mahjong tiles; he accepted my request for an interview and shop visit without an ounce of hesitation.

And for now, that’s the most he can do: share his craft with as many people as he can, before the existence of hand-carved mahjong is limited to the pages of history books.

© 2020 Mabel Lui